Berlin Chronologist

Dr. Eduard Meyer

Doubted Moses

Part Two:

Irony of Meyer’s Kantianism

by

Damien F. Mackey

“Meyer argued that the 'first fundamental task of the historian is to ascertain the

facts (‘Thatsachen '), which once existed in reality. …. He might - and this case does happen perpetually - create the nicest and most profoundest theories and combinations ... this all is of no worth whatsoever and leads the reader only astray into a world of fantasy, instead of into the real world'.”

Whilst this is good advice coming from Dr. Eduard Meyer, he himself apparently did not take it to heart as far as his chronology of ancient Egypt went, but ended up creating a mathematicised Sothic theory that achieved exactly what he was here warning against, ‘creat[ing] the nicest and most profoundest theories and combinations ... all … of no worth whatsoever and leads the reader only astray into a world of fantasy, instead of into the real world'. See my:

The Fall of the Sothic Theory: Egyptian Chronology Revisited

which is a manageable version of my MA thesis:

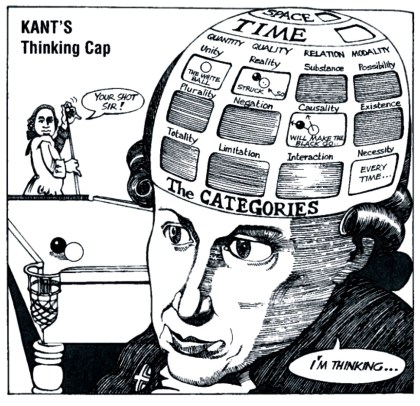

I have wondered if the German historian, Eduard Meyer (b. 1855) had, with his artificial approach to chronological reality, come under the influence of the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant (d. 1804) and his a priori approach to extra-mental reality.

Though I myself am by no means a Kantian, far my favourite book on the subject of the philosophy of science is, by far, Dr. Gavin Ardley’s Aquinas and Kant, in which Ardley gives to Kant the credit for having uncovered the Procrustean nature of modern theoretical science.

Regarding the Procrusteanisation of history, here is what I previously wrote with heavy reference to Gavin Ardley:

“… It seemed to me as nearly certain as anything in the future could be, that historical thought … would increase in importance far more rapidly during the 20th; and that we might very well be standing on the threshold of an age in which history would be as important for the world as natural science had been between 1600 and 1900”.

R. G. Collingwood, Autobiography

One may find rather illuminating - when considering Eduard Meyer’s artificially reconstructed (along Kantian lines) Egyptian dynastic ‘history’ in contrast to real objective Egyptian history - the Kantian-influenced professor R. G. Collingwood’s approach to history, as summarised by Gavin Ardley, in Aquinas and Kant: the foundations of the modern sciences (Chapter XIV: History as Science)?

Professor Collingwood

The modern progressive science of physics commenced when, in the words of Kant, we ceased to be like a pupil listening to everything the teacher chooses to say, but instead like a judge, compelled Nature to answer questions which we ourselves had formulated. It has been suggested in recent years that a progressive science of history might be started if a like Copernican revolution could be brought about in historical studies.

The late Professor R. G. Collingwood [d. 1943] was one of the leading exponents of this view. His thought is permeated through and through with Kant’s great idea about the Galilean epistemology, and he believed he could see a future for history as brilliant as the career of physics since Galileo.

He writes in his Autobiography [Ch. VIII].

Until the late 19th an early 20th centuries, historical studies had been in a condition analogous to that of natural science before Galileo. In Galileo’s time something happened to natural science (only a very ignorant or a very learned man would undertake to say briefly what it was) which suddenly and enormously increased the velocity of its progress and the width of its outlook. About the end of the 19th century something of the same kind was happening, more gradually and less spectacularly perhaps, but not less certainly, to history.

… It seemed to me as nearly certain as anything in the future could be, that historical thought, whose constantly increasing importance had been one of the most striking features of the 19th century, would increase in importance far more rapidly during the 20th; and that we might very well be standing on the threshold of an age in which history would be as important for the world as natural science had been between 1600 and 1900.

History in the past was what Collingwood calls a ‘scissors and paste affair’. This was like physics before Galileo. Collingwood writes:

If historians could only repeat, with different arrangements and different styles of decoration, what others had said before them, the age-old hope of using it as a school of political wisdom was as vain as Hegel knew it to be when he made his famous remark that the only thing to be learnt from history is that nobody ever learns anything from history.

But what if history is not a scissors and paste affair? What if the historian resembles the natural scientist in asking his own questions, and insisting on an answer? Clearly, that altered the situation.

The past with which the historian deals is not a dead past, but a past which is living on in the present. With the Copernican revolution in our approach to this living past, history, so Collingwood hopes, will become a school of moral and political wisdom.

Collingwood peaks of political ‘wisdom’ being the Baconian fruits of this revolution. But on the analogy of the natural sciences ‘wisdom’ seems hardly the right term. Terms such as power, control, utility, prediction, would be more appropriate. This really is what Collingwood envisages in other passages. He writes: [Ch. IX].

It was a plain fact that the gigantic increase since about 1600 in his power to control Nature had not been accompanied by a corresponding increase, or anything like it, in his power to control human situations….

It was the widening of the scientific outlook and the acceleration of scientific progress in the days of Galileo that had led in the fullness of time from the water-wheels and windmills of the Middle Ages to the almost incredible power and delicacy of the modern machine. In dealing with their fellow men, I could see, men were still what they were in dealing with machines in the Middle Ages. Well meaning babblers talked about the necessity for a change of heart. But the trouble was obviously in the head. What was needed was not more good will and human affection, but more understanding of human affairs and more knowledge of how to handle them.

This increase in our ability to handle human affairs, then, is to be brought about by the same revolution which transformed natural science in the 17th century, the nature of which revolution was first recognised by Immanuel Kant.

As Collinwood sees it, history as a science of human affairs did not begin to emerge until the 20th century. In the pre-scientific history age men perforce searched elsewhere for a science of human affairs. The 18th century looked for a ‘science of human nature’. The 19th century sought for it in the shape of psychology. These both turned out to be illusory. But since the revolution in history, history has revealed itself as the one true science of human affairs. [Ch. X].

The Two Histories

We might point out, however, something which Collingwood does not make clear, and about which he was probably not at all clear himself. This is the matter to which we drew attention when we doubted the appropriateness of the word ‘wisdom’ for the knowledge acquired through the new science of history, and suggested such epithets as control, power, utility, etc., in its place. For, as we have insisted throughout this book, the fact that we have a Procrustean science does not mean that we have in any way abolished the structure of Nature, or that we can no longer know Nature in the way in which the philosophia perennis knows it.

Collingwood’s proposed Kantian revolution in history will give us, of course, a Procrustean categorial science of history. But real objective history will carry on just as before. The relation between the two will be like the relation of modern so-called ‘physics’ to real physics, i.e. of nomos to physis. [cf. e.g. modern sociology on the one hand and ethics on the other (Ch. XIII), or Freudian therapeutic psychology and rational psychology (Ch. XV)]. The term ‘wisdom’ is more appropriate to knowledge of the physis than to the categorial structure devised by the ingenuity of man. The latter, in the case of history, is a practical instrument of manipulation for the prince, the former is the pursuit of the real nature of history.

The Character of Scientific History

Collingwood laid down the general principle which must be followed if history is to become a science, but he did not pursue the subject into specific terms.

We might develop a scheme of procedure in history by following the analogy of modern physics. This suggests the introduction into history of laws, fictions, artificial constructions, etc., as in physics. The concepts of ordinary life must be replaced by others more convenient for our purpose. For instance, in the exact physical sciences, the English term ‘hard’, which is a familiar and vague expression, is replaced by a number of artificial but exact terms, such as malleability, shear modulus, tensile strength, etc. This would lead to a monstrous jargon in history akin to the formidable technical terminology of the Procrustean natural sciences. The new Procrustean history would now be only for specialists and would soon become as unintelligible to the layman as is modern physics. But its justification, if indeed it could be constructed, would be the pragmatic sanction of practical utility. It would be a handy machine for princes. It should be remembered too that the new history would be potentially a dangerous weapon, just as dangerous, if not more so, than the control we now possess over inanimate Nature.

Whether such a Procrustean scheme will ever be born remains to be seen. For the inherent tractability or intractability of the raw material forming the primary subject matter of the Procrustean science must have some bearing on the ease with which such a science can be developed. The Procrustean method has had its greatest triumph in modern physics. In the biological sciences it has made much less progress, and in the human sciences and history has hardly started. Is this comparative failure outside physics due merely to dilatoriness and ineptitude, or is there a more underlying cause: that the subject matter in the animate and rational worlds is so much more intractable that it does not lend itself to Procrusteanisation?

If a Procrustean history does emerge, as Collingwood hopes, there may possibly be in consequence an initial reaction away from classical history, like the reaction away from Aristotelian science, and indeed all things Aristotelian, in the times of Galileo. But such a reaction in historical studies would be as ill-founded as was the 17th century reaction.

Let wiser counsels prevail, and the two pursuits may go on side by side. To prevent confusion of the two, which caused so much trouble with the old and new physical sciences, it would be better to find a new name for the new Procrustean history. To go on calling it ‘history’ would be a perpetual source of confusion with real history. We would suggest the term nomics except that we have already applied that term to post-Galilean ‘physics’. No doubt some new term appropriate to the situation could be found.

[End of quotes]

Now I believe that the same type of artificial process has been applied by chronologist Eduard Meyer to ancient Egyptian chronology, which then became the yardstick for the chronologies of other ancient nations. With disastrous effect! (See e.g., Peter James’s Centuries of Darkness, 1990).

Dr. Meyer, endeavouring to bring some type of mathematical (astronomically-based) order to the highly complex Egyptian chronology (30 dynasties), imposed his pre-conceived system which, unfortunately, has no compelling basis in reality.

And Kant himself, mistakingly thinking that this ‘a priori’ approach is how the human mind actually works, went on to develop an epistemology, a pseudo ‘metaphysics’, that - whilst it may be neat and convenient - is actually no more real than is Meyer’s Sothic system.

Well, according to the following article, Eduard Meyer did indeed come under some degree of Kantian influence: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4321/1/2001ReibigPhD.pdf

Reibig, André (2001) The Bücher-Meyer controversy: the nature of the

ancient economy in modern ideology (pp. 67-70).

….

Diametrically opposed to Lamprecht's putative laws of 'mass-psychology', Meyer's own position is at first glance firmly rooted in the established tradition of German idealism àla Ranke and Kant. The Kantian influence on his philosophy came to light with the emphasis on the centrality of 'free will' (freier Wille) and 'accident' (Zufall) as a core notion of the historical enquiry. ….

Accident in history, for Meyer, is not to be understood as if a particular event did not have a cause. However, because of the fact that every action or event can be seen as being an effect and a potential cause at the same time, every human being faces the problem of reducing the occurrence of an event down to a finite number of causes. This is impossible for Meyer unless one reduces every event down to one ultimate and first cause: God, for instance. Yet this would only constitute a prima facie proof. Accident and free will undeniably have their place in human epistemology. As it was for Kant, Meyer also believed that man is capable of willing his own actions. The ability to will one's actions freely - the capacity of self-determination, is a proof of the epistemological existence of such a 'free will' . …. In this way, the historian is not interested in the causes of actions or events but in reasons, which are not reducible to a single overpowering force. Yet this is not to say that Meyer would deny the existence of physical or 'ideological' determination of an event. This causal analysis, besides its validity and scientific attractiveness, is however not the nature of the historical explanation proper. …. The historian's task is to give a teleological explanation; he seeks to grasp what a certain decision or event could have aimed at, and not primarily what caused it. Meyer's compatibalist view of the human will as both free and determined does not create a putative contradiction between accident and necessity, since they do not exist within the objects themselves. The latter are still subject to causality, but accident and necessity are properties of the categories, under which we subsume the particular phenomena ('Erschreinung '). ….

However, Meyer's analysis of the epistemological existence of 'free will' and 'accident' to which he devotes a good half of the THEORIE (pp. 5-34), appears elusive; in its quest to defend the fundamental importance of subjectivity and individuality in history it forms primarily a polemic against Lamprecht. …. For Meyer one of the many examples used in order to elucidate the possibility of 'accident' and 'free will' as predominant and an epistemological necessity in history, is the outbreak of the Second Punic War. According to Meyer, the historian should not consider primarily external causes, but rather treat them as results of a conscious decision (‘Willensentschluss '). …. Therefore, history deals with the analysis of the particular event; judging its importance by whether it had an impact on the world of human affairs, primarily politically but also culturally. Directed against his opponents Meyer argued that the 'first fundamental task of the historian is to ascertain the facts (‘Thatsachen '), which once existed in reality. If he does not follow this task ... if he does not know the particularities of the event...then his endeavour is nonrepresentational ... He might - and this case does happen perpetually - create the nicest and most profoundest theories and combinations ... this all is of no worth whatsoever and leads the reader only astray into a world of fantasy, instead of into the real world'. ….

Besides confining the primary task of the historian as basing his interpretation on the facts, Meyer lashes out once more against his opponents in the familiar guise of Karl Lamprecht and Karl Bücher. His accusations against them can be summarised under three points. First, to attempt to form generalisations about 'history life', which take a similar shape to the laws of natural sciences; laws can never be the object of history but only the precondition. Instead, 'the object of history is everywhere the enquiry and representation of the particular event' - 'the individual' ('das Individuelle '). …. Secondly, that they sought to deny the 'predominant influence of accident and the will of the individual personalities ... on the thoughts and views of the individual and the masses'. ….

Third, he complained that they aimed to 'postulate the dominant importance of mass phenomena, in particular economic 'laws', even though it is obvious that the whole economic development of wealth and the social shaping of a state or people (Volk) is dependent on political impulses' . …. For Meyer, the main error lies in the 'the idea of monism in the scientific world-view' and secondly in the geographical and mass-psychological approaches. …. Meyer highlights instead that the centrality of the event forms the basis of Ereignisgeschichte, ('event history'), which consists primarily in the documentation of facts. However, from generation to generation, history would put an ever-increasing burden of facts upon mankind, facing us with the problem of handling its sheer quantity. This Kantian consideration played an important part in Meyer's interpretation of antiquity. Friedrich Nietzsche, who became popular at the turn of the century, suggested that history should only be pursued for the sake of its usefulness to our present situation and not as an end in itself. This would mean that the historian's task does not exhaust itself in the occupation of the archivist or the heraldic story writer, but also in the critical investigation of the particular worth or value of an event or fact for our present. Such an analysis can only take place if the historian himself possesses the correct historical worldview. …. Meyer argued that the selection of what is historically important involves directly the present interests of the historian in 'what was effective and influential. …. He understood too that the interests and value judgements of the historian also come into play in his interpretation of historical events. …. Immediately, the question comes to mind as to what kind of criteria should the historian apply in order to distinguish between what has been influential and what has been trivial or worthless? At this point Meyer's methodology faces substantial difficulties. 'The answer can only be taken from the present; its selection lies within the historical interests, which have some kind of an effect onto the present'. …. Therefore, the starting point of the historical investigation has to be always the present, whereas the historical presentation starts with the earliest findings. …. Yet Meyer shows openness as to what this field of interest may be, which may catch the historian's attention. 'Sometimes it's this, sometimes it's that', he says, 'which appears in the foreground, politics, religion, economic history, literature and art and so forth. An absolute norm does not exist'. …. The only deterrent is therefore solely its effect on the particular present. At first glance it looks as if such a philosophy would create a scientific basis to allow any individual, state or nation to become the subject of historical investigation, however Meyer's whole endeavour runs into difficulties when he tries to assess which questions are important for the understanding of present. He wonders, since the future has not yet happened, how can we indeed assess which historical moments are able to enlighten us and which once may lead us on the wrong path? As for the historical personality, the historical event can be anything that the historian declares as important when determining the cause for a particular political decision made in the present. A historical tool such as this could be open to abuse and would not equip us with a standard to judge whether the historian has picked the 'right' events or not. However, Meyer does not allow for such an arbitrary and subjective selection, which would only lead into historical relativism. He argues that the 'more far reaching the circle of the effect of a particular historical event, the more important it is and the greater is the interest which we assign to it'. ….

No comments:

Post a Comment